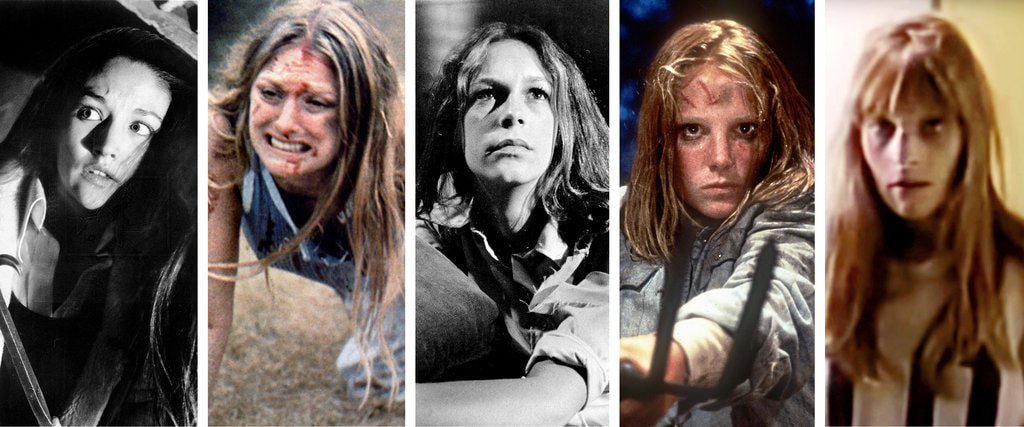

In horror movies and sometimes survivalist themed films, it is a common and much celebrated cinematic convention, to have the last hero standing, be a virtuous, unassuming kind woman. She is typically the one person in a group dynamic, that we wouldn’t bet on surviving if the apocalypse came tomorrow, yet she becomes the one that remains - she becomes; The Final Girl and internationally, she is one of the most recognised motifs in cinema.

The term Final Girl was first coined by Carol Clover in 1987, when she wrote an essay called “Her Body, Himself: Gender in the Slasher Film” which was later mentioned in her 1992 book “Men, Women and Chainsaws: Gender In The Modern Horror Film”. Predominantly cited as a feature in the Slasher genre of horror film, my own observations of the final girl heroine, usually had her be a weak, unskilled and unknowledgeable person. Yet ultimately, the final girl seemed to be empowered, even protected by her innate goodness or 'pureness', perhaps stemming from a sub-conscious, puritanical Judeo-Christian reason, as to why she should not die. Male filmmakers, with their construction of the female archetype, I imagine wanted the peril to be absolute and so by pitting a thoroughly malevolent male-energised force against someone who looked like they couldn’t punch their way out of a wet paper bag, they had to encapsulate the complete opposite. Remember the rule about couples who have sex or do 'bad things' in horror movies...well that outlook in part seems to manifest in the final girl's construction and so we are given an inexperienced female as a norm, with no radical life experience or formidable nature.

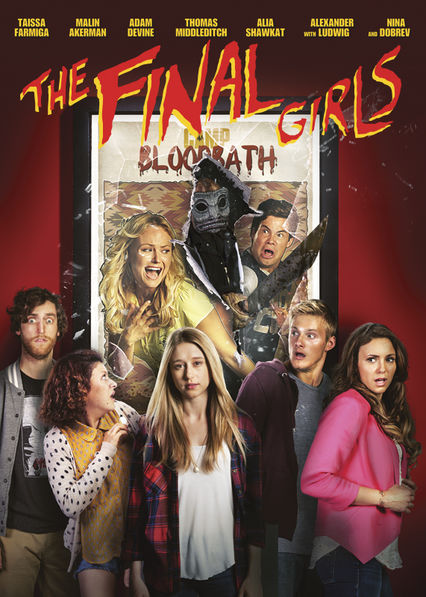

Not to say; that there were never any exceptions to the rule, but in the early days of horror, the bog standard archetype of the final girl was almost guaranteed. However, it began to change when less obvious forms of the Slasher horror began to emerge, usually in movies that spliced the established part of the genre with something totally unrelated. Modern films like Happy Death Day (2017) which has time travel within its narrative and The Final Girls (2016) which has characters sucked into a movie, are high-concept films, with Science Fiction and Fantasy elements. Not only have they helped sustain and elevate the genre, they have added to the characterisation roster of what a final girl can be. But, they owe their allowed existence to pioneering and isolated works from previous decades, as it was back in 1979, when Alien, a Sci-fi Slasher film set in space changed the game. Now I can hear you thinking "Alien", a slasher movie?" Well think about it - we have the mandatory tight group confined to a particular locale. We have the malevolent force, killing the group off one by one. We have the early parts of the film establishing personality types, leadership and skill qualities and we have the cast in itself, which served to make you think about who would survive, as surely the producers wouldn’t allow the big stars to be killed - right? No one saw a final girl premise being implemented and no one saw Sigourney Weaver coming either. A virtual unknown, Alien was Weaver's second ever big screen role and her first role in Annie Hall (1977) was a small non-speaking part. As the surprise lone survivor of the Nostromo incident, this was probably one hell of an unexpected direction for the movie and it is no surprise that Weaver was the last person to be cast. The gamble paid off and audiences loved and continue to love Ripley, a final girl who was neither timid nor exceptionally strong, who had skills, knowhow, and a quite charm that allowed us to see her as a real human being.

What is interesting about the format of Halloween, is that the tight knit group that we are use to seeing in Slasher's, didn’t really exist here, there are no scenes where they all become alerted as a group to whom the big bad is and then unite as a team to fight it. Instead, the bogeyman Michael Myers is stealthy, no one notices him (except for Laurie) leaving everyone to roam around as normal and to be picked off one-by-one in isolation. In films like I Know What You Did Last Summer (1997) or Final Destination (2000) the group usually (eventually) becomes aware of the evil and they band together to fight it off, which contributes to the drama. In Halloween, all of Laurie’s 'group' are killed before she truly encounters Michael which in itself is horrifying because of the ignorance of a nearby, but unseen danger. Even in fighting back, we still see that the final girl trope is in its infancy, as it is a male hero, Doctor Loomis (Donald Pleasence), enters the scene in the nick of time and ‘ejects’ Michael through a window. 40 years later and the situation comes full circle, where now Laurie Strode is well versed in all things Michael Myers and has a skill set akin to that of a militia warrior to deal with him. Sarah Connor in the The Terminator (1984) could easily be compared to Laurie Strode, as both Michael Myers and the T-800 series cyborg are two unstoppable forces, with similar mindsets, hell bent on killing one person and not averse to killing anyone that gets in the way of their mission. And just like Laurie empowers herself years later, Sarah Connor, in T2 Judgement Day (1991) also expands as a character, having evolved into a gun-toting, trap-setting bad ass too.

Appearing in three of the NOES films, Nancy uses her brains to try and combat, not so much Freddy Kruger at first, but falling asleep. When this becomes too hard, she relies on uncovering the personal legend behind Krueger and then discovers her own supernatural power somewhere in the process. Nancy Thompson may also be the first final girl to outwit a supernatural foe, which may have been the prototype that led to so many other movies taking this route. Instead of meeting force with force, solving a mystical conundrum, revolving around the villain's mythology became the solution. A lot of thought went into understanding dream psychology and fear, drawing on the night terrors that humans truly have and so this gave the earlier entries of the NOES a more respectable standing and potency. In NOES 3 – Dream Warriors, we get one of the most organised and unified team of victims ready to fight back and they are all imbued with powers to fight the evil. This made the plot fresh, as most horrors needed the victims to be completely powerless and have the audience empathise with their total helplessness and jeopardy. But even in knowing that each character is headed for their own personal gallows, the ace in the hole was in crafting bespoke deaths, that directly linked to a character's personal fears and trauma and with the exception of the Saw films, I don't think any other franchise or one shot film ever made the life of a character so connected to their death. The Wishmaster films are another bunch of stories that rallied around the idea of the final girl using cunning and trickery to resolve the peril, making audiences think as much as they did jump.

Away from the Slasher genre, another angle of exploration, came courtesy of character Kirsty Cotton’s approach to dealing with the Cenobites in Hellraiser (1987). Using the power of negotiation, Kirsty had to deal with a well-spoken evil that actually had manners and her encounters with Pinhead provided an eerie contrast for viewers because the confrontations were verbal, very still but extremely tense. We all knew that the Cenobites didn’t have to listen to anyone’s pleas to seek a civil audience or show anyone, any mercy, but in examining the personality of the Cenobites' Kirsty saw their weakness and appealed to their hubris. Exploiting a very human emotion she tells them of an escapee from their subterranean cells and in their utter disbelief that anyone could escape them - their power, she is able to trade her life for his. In the second entry Hellbound: Hellraiser II (1987) her words are used to remind the Cenobites of their former humanity, showing the audience that we are all not that far away from being the horror or the hero ourselves. As a final girl, Kirsty was great at thinking on her feet, rather than just using them to run.

What was interesting about Scream (1996) was it’s unapologetic ode to all the conventions of the Slasher film, by talking and examining the rules of the genre within its own narrative. A direct message to the audience that; we know what you’re expecting and you won’t be seeing that here, prepared us to be tricked and misdirected throughout each entry. The Scream endings might have been inspired by the likes of films like Sleepaway Camp (1983) and April Fool’s Day (1986), where the reveal is just as important as the scares. Scream also has a lot in common with a whodunit mystery drama, with final girl Sidney Prescott being depicted as intelligent, calm and resourceful, traits closer to a detective, than a person purely present to be in peril. Scream also allowed recurring characters, from the original central group to return - yes! Those who by default should have been killed returned for multiple sequels.

As the final girl motif continues to stay with us, it also continues to evolve. Modern depictions of the final girl have permitted us, even forced us to have a range of characterisation that can give us all types of personality. But who ever takes the mantle of the final girl, we know that she is going to be chased, cut, shot at, tortured, petrified, made to scream and made to witness death. But we also know that she will fight back, ultimately instilling hope and promoting self-reliance.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed